The Drawings Of Susan Te Kahurangi King

U pstairs at the Marlborough Contemporary, a woman bows over a pad of headed notepaper. She doesn't look up when the door opens. She picks a fluorescent highlighter from a heap in her lap and with the broad side of the nib blocks out a quad of blue or green – close, companionable colours. Then she picks up another pen and moves on to a new quad. She fills the page methodically, a thin white rim around each swatch. She doesn't look up, and she doesn't stop until the paper is complete.

Susan Te Kahurangi King is 66 and she has been drawing since she was a young child. For decades the marks that streamed out of her pen have been her prime means of expression, because at around the age of four, King stopped speaking. By the age of nine she had stripped her verbal communication down to an occasional word. At 10, her grandparents were discussing a funeral they had been to, and Susan broke her silence to say: "Dead. Dead. Dead." It is the last thing anyone remembers her saying.

Sometimes as a child, she hummed or sang as she drew. But when the family introduced her to people, where she grew up in Te Aroha, in rural New Zealand, they'd say, "This is Susan, she doesn't talk, but she does great art."

King's family have always appreciated her work. But it is only in the last few years that she has broken into the commercial world with her first exhibitions at the Outsider art fairs in Paris and New York, and at the ICA Miami. Thousands of miles separate where Susan lives with her sister Wendy, her main carer, in Hamilton, New Zealand, and New York or Dallas, where the freelance curator Chris Byrne divides his time. But one day Byrne was chatting with his friend, the artist and illustrator Gary Panter. Panter mentioned King – he'd come across her work on Facebook – and after the two men had said goodbye, Byrne looked her up. It was like viewing a Philip Guston, he says. "There's an immediacy there. I knew it so quickly. As a draughtsman she is off the charts, as an image-maker too."

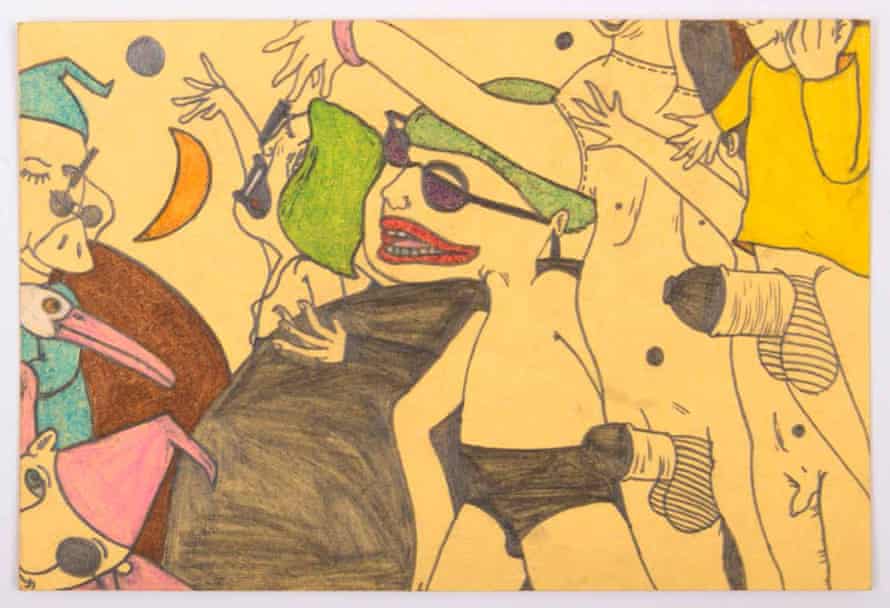

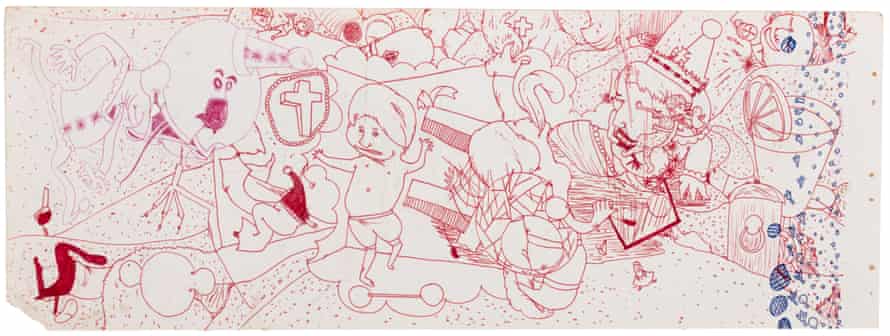

Byrne has curated all of King's shows. Some of the 32 works exhibited at the Marlborough Contemporary gallery, with their tightly segmented shapes, faces and body parts, tessellate like vibrant, jagged jigsaws. More recent works resemble intricate mosaics. Many childhood drawings depict a nightmarish party, peopled by Disney characters, "Fantaman", and occasionally the Queen. "The vocabulary is expansive, cumulative. Susan doesn't scale things up. What's happening is happening," Byrne says. "It's almost like she's transcribing something. Even though her line is very direct and consistent, there's no in-between steps."

King never plans, never uses an eraser. Interestingly, given her silence, there are a lot of open mouths. And a lot of phallic imagery. (Recently the family found, tucked into Susan's late grandmother's diary, six detailed sketches they refer to as "the penis drawings".) "Who knows what she's seen where?" says her younger sister Petita Cole, who manages the art side of Susan's life, when I ask her about this. "Mum used to say 'Look, you know, the hospital people when she was staying in the psychiatric ward, they were doing anything to get a reaction from her.'"

For all the cartoonish smiles, there is something concerning and dark about these works. Among the noise of high-volume colour, there's a space for gentler pencil strokes, and occasionally a quiet, still figure emerges from the chaos. Sometimes King draws with a white pencil on white paper, or black on black, as if her nib is searching for a privacy on the paper.

King grew up the second child of 12. "Occasionally Dad would have a shower and he'd walk from the shower to his bedroom nude," says Petita. "So she's seen Dad and she's seen the younger boys. As far as the balance of what's in the drawings, she's got those and then she's got all the magnificent birds and insects."

At five, her teacher raised concerns about her silence, triggering a long and faltering investigation into King's muteness. Eventually, the family moved to Auckland to be within reach of an IHC school for children with learning disabilities, which King continued to attend long into adulthood. But Petita believes that the school hampered her sister's creativity. It was a case of, "Come on, you're grown up now, we're not doing art!" Instead King spent her days on assembly work, fitting the cardboard bit inside the lid of Nutella jars.

The repetitiveness of her daytimes began to impact on King at home, where she started to display signs of OCD. She would move the tap to get it lined up right. She took to shutting the windows and fixated on loose threads. She would pull and pull, cut, and wind them up with other loose threads. Years later, when Petita saw the works of artist Judith Scott, she thought, "My gosh, these things that Susan had made, we never saw them as a form of art!". But at the time, Susan's disquiet troubled her. "They weren't done with a smile on her face, they were done as part of an anxiety. It was like, I found this thing and now I've got to wind it, and now I've got to find more, and then I've got to wind it."

We are talking with Susan beside us, but she doesn't look up; she knows no sign language, never even points. Occasionally, she swings her feet and soon, possibly tired, she leaves the room.

Susan's behaviour, her silence, her notable differences, had always perplexed her family. Perhaps because of this, nothing she produced in childhood was thrown away. Her family has been building her archive her whole life - initially at least, in the hope of understanding her better. "Everything was kept because it was like, 'If a doctor were to see it, maybe that would help explain things'," Petita says. It is only over the past decade, when Petita took on a job teaching children with autism, that she realised that Susan probably had the condition. She was finally diagnosed in 2015.

Petita, meanwhile, had decided that a proper archive was in order. She began to sort through Susan's work. "They were just stored at home in boxes and old cases, and rolled up and put in the rafters." Corners were bent or torn or crimped from the lids of cases. One sibling had made a scrapbook of Susan's work and folded, trimmed, glued and taped drawings on to the page. "Broken all the rules!" Petita opines. So Petita stacked the drawings according to which size file they could be stored in and "began the cataloguing".

To give an indication of Susan's output, Petita now holds at least 20 A4-sized folders in custom-made cabinetry in an archival room at her home in Northcote. Each has 100 pages. And that's just up to 1992. (After 1992, Susan stopped drawing for 15 years, partly, Petita thinks, owing to the regimentation of life at the IHC school.) There are also A3, A2 and A1 folders for both before the hiatus and after it. You could try to do the maths, but the answer is in the thousands.

It is Byrne, with Petita's assistance, who selects the works for exhibition; Susan herself has no understanding of the concepts of either ownership or selection, Petita says. Initially the family rule was that the drawings could be shown but not sold, though they have since relented. "Think about it," Petita told her sisters after seeing Byrne's careful framing for the Miami exhibition last year. "When the show is over are we going to say, get them out of those frames, send them back here, they belong in the clear files on my shelves?"

By now Susan has finished her highlighter sketch. Petita takes the headed notepad; that one, too, will likely find its way to the archive.

- Susan Te Kahurangi King is at Marlborough Contemporary, London, until 1 July. Drawing with Susan, a silent drawing workshop, takes place there on 3 June from 3-6pm.

The Drawings Of Susan Te Kahurangi King

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/may/31/susan-te-kahurangi-king-silent-outsider-art

Posted by: yeltonthationothe.blogspot.com

0 Response to "The Drawings Of Susan Te Kahurangi King"

Post a Comment